News

-

How we are Protecting and Keeping our Staff Well this Winter

18 December 2025

-

Carols Round the Christmas Tree

18 December 2025

-

School Nursing Excellence Celebrated at National SAPHNA Conference

17 December 2025

-

Celebrating Multiple Wins At The CIO Live Awards 2025

12 December 2025

-

Trust Christmas Trees in Beverley Minster

12 December 2025

-

-

Interweave win at HFMA Awards

09 December 2025

-

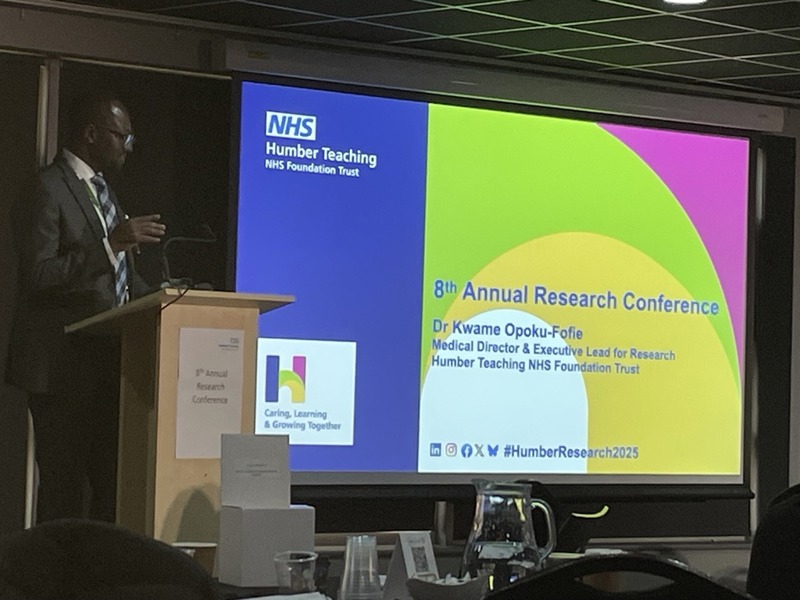

Humber Research Team Conference 2025

09 December 2025

-

Celebrating our Humbelievable teams at the 2025 Staff Awards

05 December 2025

We held our annual Staff Celebration Event to celebrate the fantastic and innovative work of our teams and staff.

-

Recognising the volunteers who go the extra mile

25 November 2025

-

-

-

Bring a little festive joy to people in hospital this Christmas

12 November 2025

-

Next step in GP transition agreed

05 November 2025

-